100 Years: The Evolution of the Electoral College Map

A Century of Drama and Surprises. Plus, a Peek into the Crystal Ball.

Welcome! If you find this article interesting, you can help me tremendously by giving it a ❤️.

The results of the 2024 Presidential Election have added yet another fascinating chapter to the story of the Electoral College map. In the aftermath, half the country was popping champagne and planning victory parades, while the other half was Googling "how to move to Canada" and stockpiling canned goods. Nowadays, democracy seems like the ultimate reality show we can't stop watching.

No matter which side of the aisle you happen to sit on, let us remind ourselves that the pendulum will continue to swing.

While researching for my documentary One Person, One Vote? about "the untold story of the Electoral College," I unearthed a mind-numbing mountain of information—most of which never made it close to the editing room.

Luckily, this publication gives me the perfect excuse to share some juicy tidbits and pester you with them with glee–such as how the Electoral College map has transformed over the past century as states have gained, lost, and swapped political identities like teenagers trying on new outfits. To make things more fun, I’ve included campaign videos from the winning candidates—remarkable snapshots of the issues and moments that defined their times.

Let's dig in. Shall we?

Because of the Electoral College, a handful of swing states are the belle of the presidential election ball. Candidates woo them with endless visits, VIP treatment, and showers of campaign dollars. States like Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and Arizona have become the equivalent of prom royalty, leaving the rest of the country to snack on stale pretzels in the gym. But can you imagine a time when almost the entire country was in a state of swing?

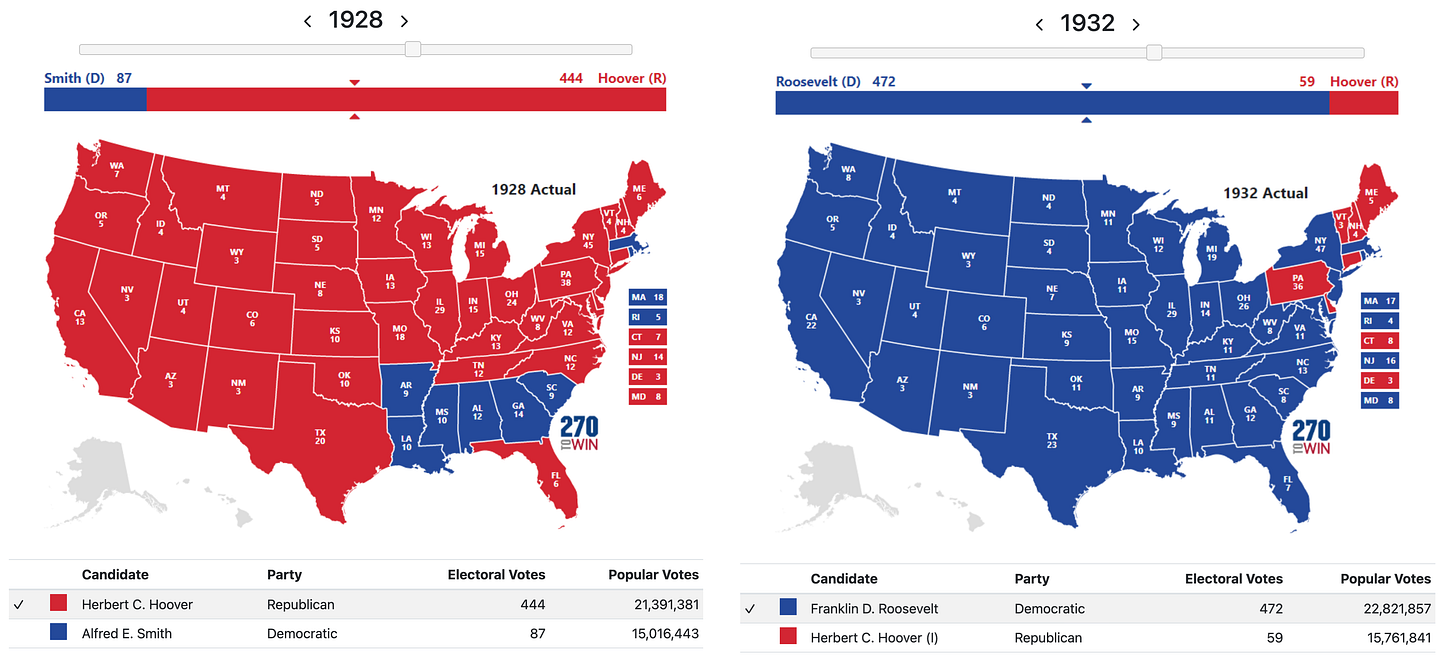

1928 and 1932 Elections

With the polarized politics of today, it is difficult to conceive of a time when almost the entire country swung from one party to another. The Electoral College map underwent a dramatic transformation between 1928 and 1932. In 1928, Herbert Hoover's landslide victory turned the map solidly Republican. By 1932, however, the Great Depression and massive unemployment had Americans giving Hoover a big "No, Thank you," paving the way for Franklin D. Roosevelt to sweep in with his New Deal and a promise to fix the mess.

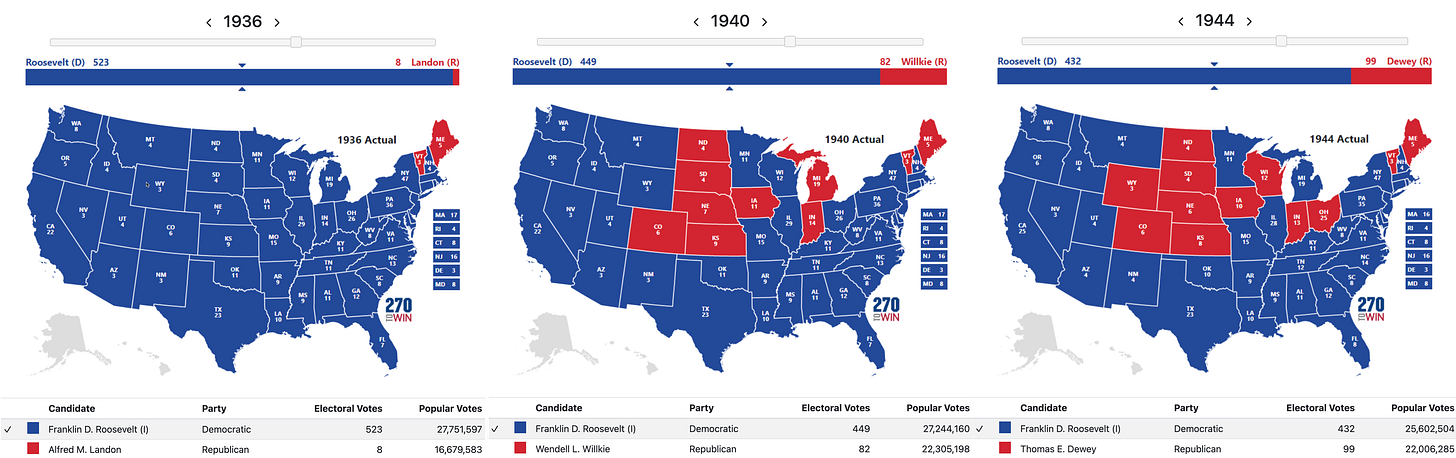

Roosevelt would lead the nation, winning an astounding four elections in a row (1932 -1944). After his presidency, Republicans in Congress pushed through the 22nd Amendment, limiting presidents to two terms.

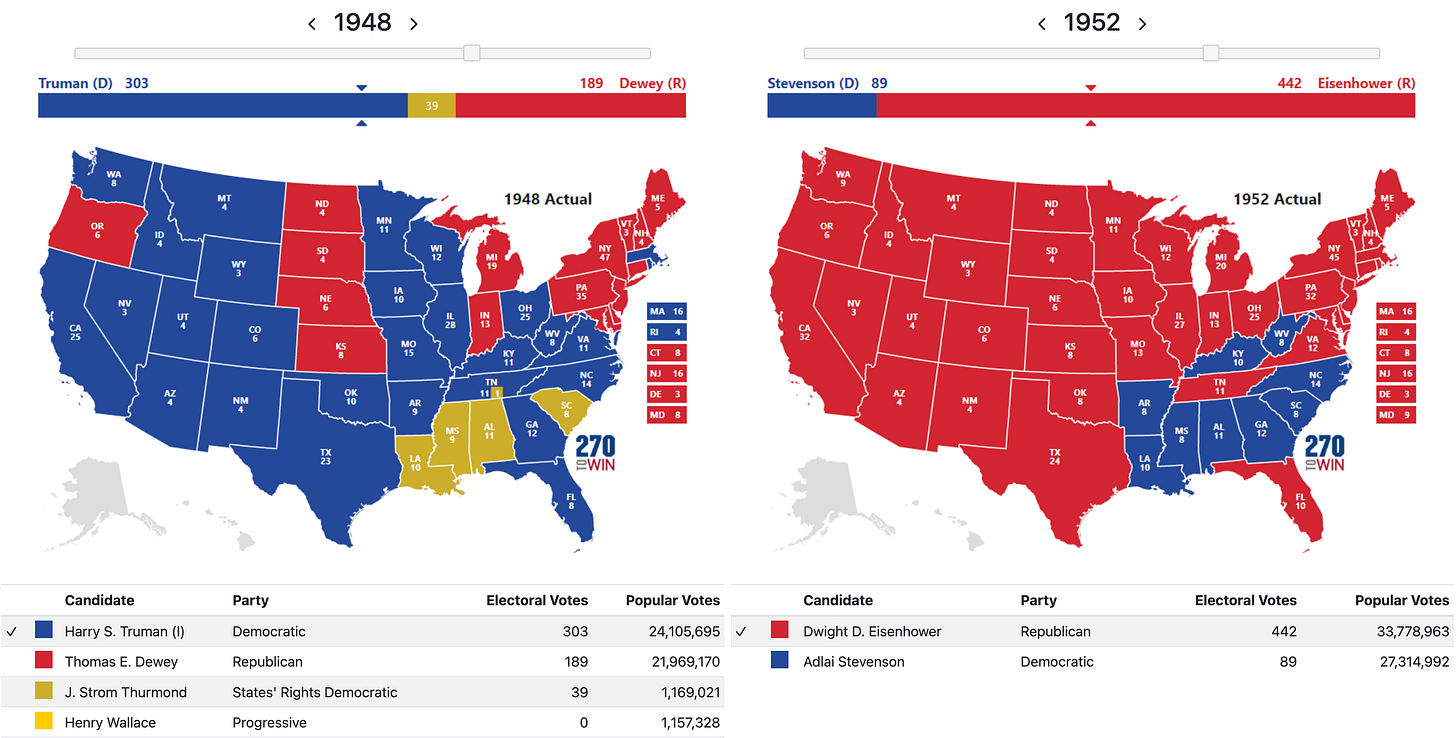

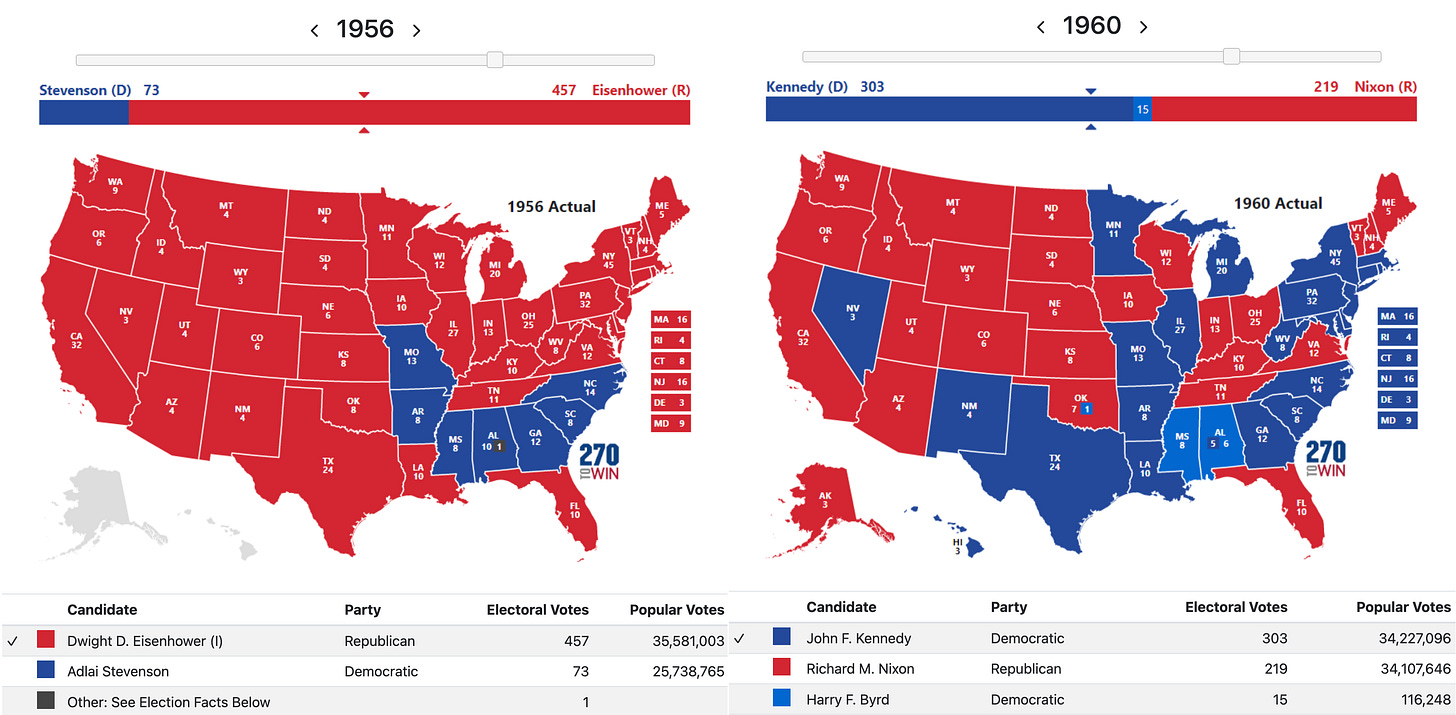

The 1952 Election

Dwight Eisenhower, a war hero (with no political baggage) who led Americans to victory in World War II, made political marketing into an art form with his catchy Republican campaign jingle, "I Like Ike.” Eisenhower ended a 20-year run for Democratic presidents in the White House (no party had done that since the end of the Civil War).

States overwhelmingly voted Republican, except for the "Solid South," a group of former slave states that almost always voted for Democrats after the Reconstruction era. This loyalty stemmed from two key factors: Black citizens were disenfranchised and unable to vote, and the white majority blamed Abraham Lincoln’s Republican Party for the Civil War and the abolition of slavery.

But with Eisenhower's military heroics and moderate Republicanism, a few Southern states started reconsidering their loyalties, foreshadowing the shift to the Republican "Red South" we know today.

The 1960 Election

A drama for the ages. It marked a pivotal moment in U.S. politics, as the charismatic John F. Kennedy and Richard M. Nixon went head-to-head in one of the closest elections in history. Kennedy was also the first Roman Catholic to be elected president.

Though Nixon was not convinced he lost the election, he graciously conceded, telling a journalist, “Our country cannot afford the agony of a constitutional crisis.”

Kennedy did manage to regain some of the South that Eisenhower had won, partly thanks to his running mate, Lyndon B. Johnson, of Texas. But real cracks were forming in the Democratic stronghold. Kennedy squeaked by with a razor-thin victory in a few states but won a significant Electoral College victory, 303 to 219.

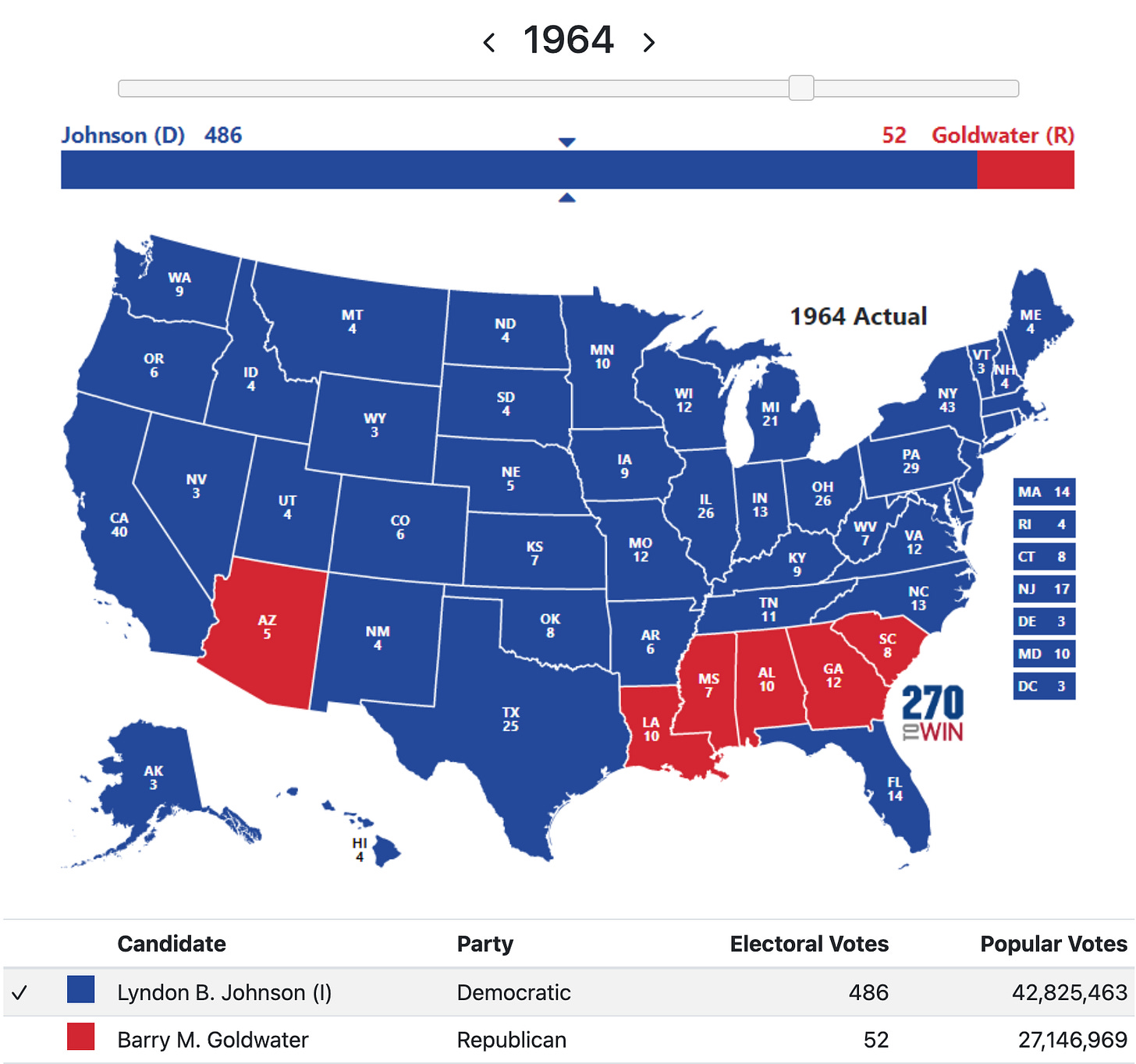

The 1964 and 1968 Elections

In 1964, Lyndon B. Johnson trounced Republican Barry Goldwater, turning the electoral map into an overwhelming ocean of blue. Johnson's "Great Society" programs and connection to JFK's legacy carried him to a landslide victory, as Goldwater's ultra-conservative platform, including his opposition to the Civil Rights Act of 1964, alienated much of the country.

Johnson snagged 44 states, leaving Goldwater with just six—his home state of Arizona and a cluster of deep South states that were still heavily segregated and where Blacks were almost entirely disfranchised. In these states, his opposition to civil rights found an audience.

But the South's newfound redness wasn't just a one-off. It was the first hint of the end of the "Solid South." Change was coming, but no one knew how big it would be. The deep South was still mostly solid, but it no longer supported the Democratic Party, which supported civil rights and an end to segregation.

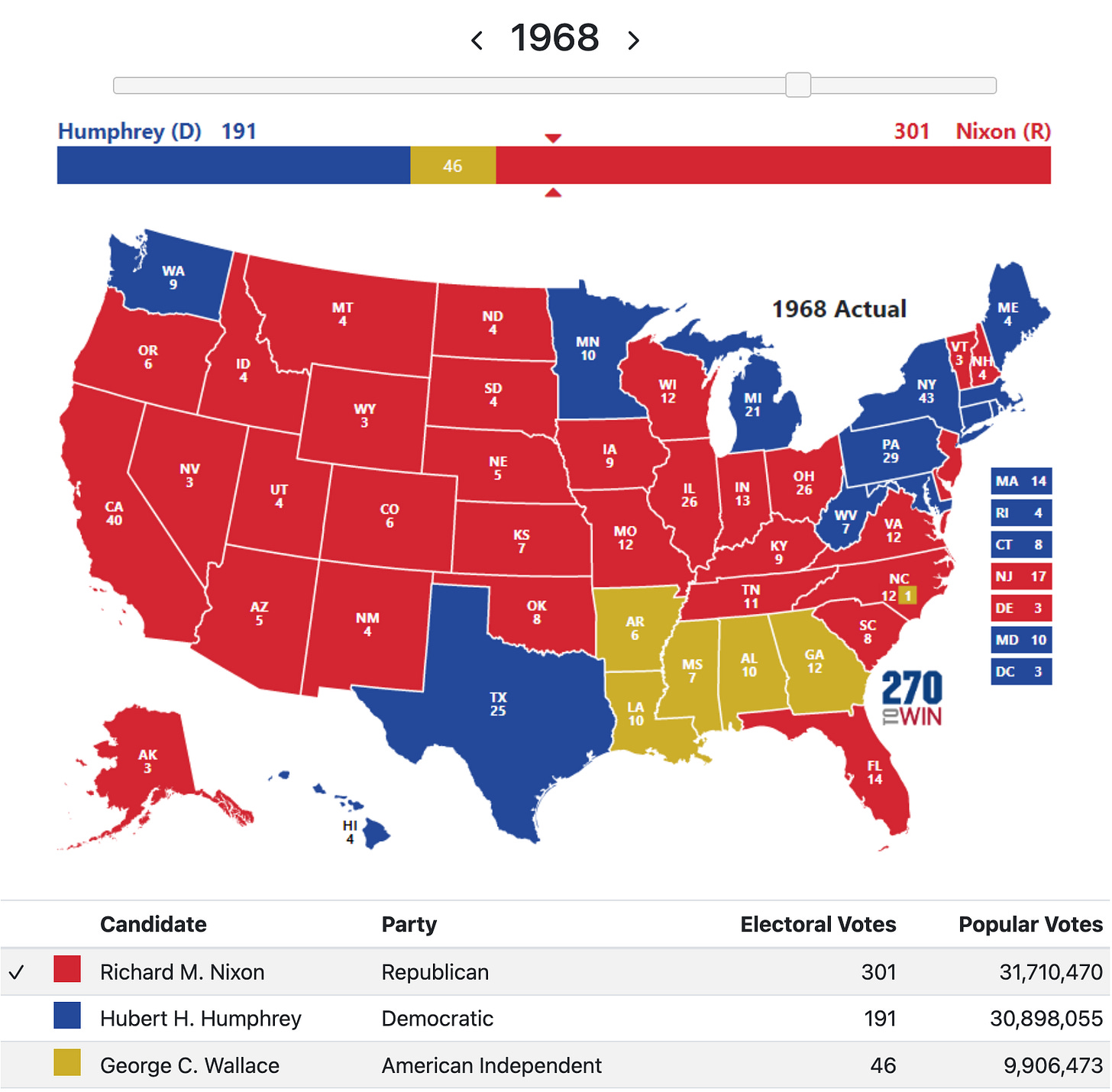

By 1968, the calm of 1964 had been replaced with absolute chaos. The Vietnam War dragged on, protests erupted across the nation, and the Democratic Party's internal drama with intense disagreement over its stance on Vietnam. Former Vice President Richard Nixon promised "law and order" and pitched himself as the candidate of the "silent majority” (a cohort of Conservative voters who keep silent in the public discourse). These phrases are also perceived as “dog whistles.”

Nixon turned much of the West and Midwest red, while Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey, the Democratic candidate, clung to the Northeast and parts of the Midwest. But the real curveball came from George Wallace, the segregationist governor of Alabama, running as a third-party candidate, who won five deep South states, four of which had voted for Goldwater in 1964. Wallace's win in the South made it clear the Democratic Party's decades-long grip on the region was over. The South was now up for grabs. Nixon developed a fear-mongering "Southern Strategy," based mostly on appealing to White segregationists, and laid the groundwork for a Republican surge in the coming decades.

The 1972 and 1976 Elections

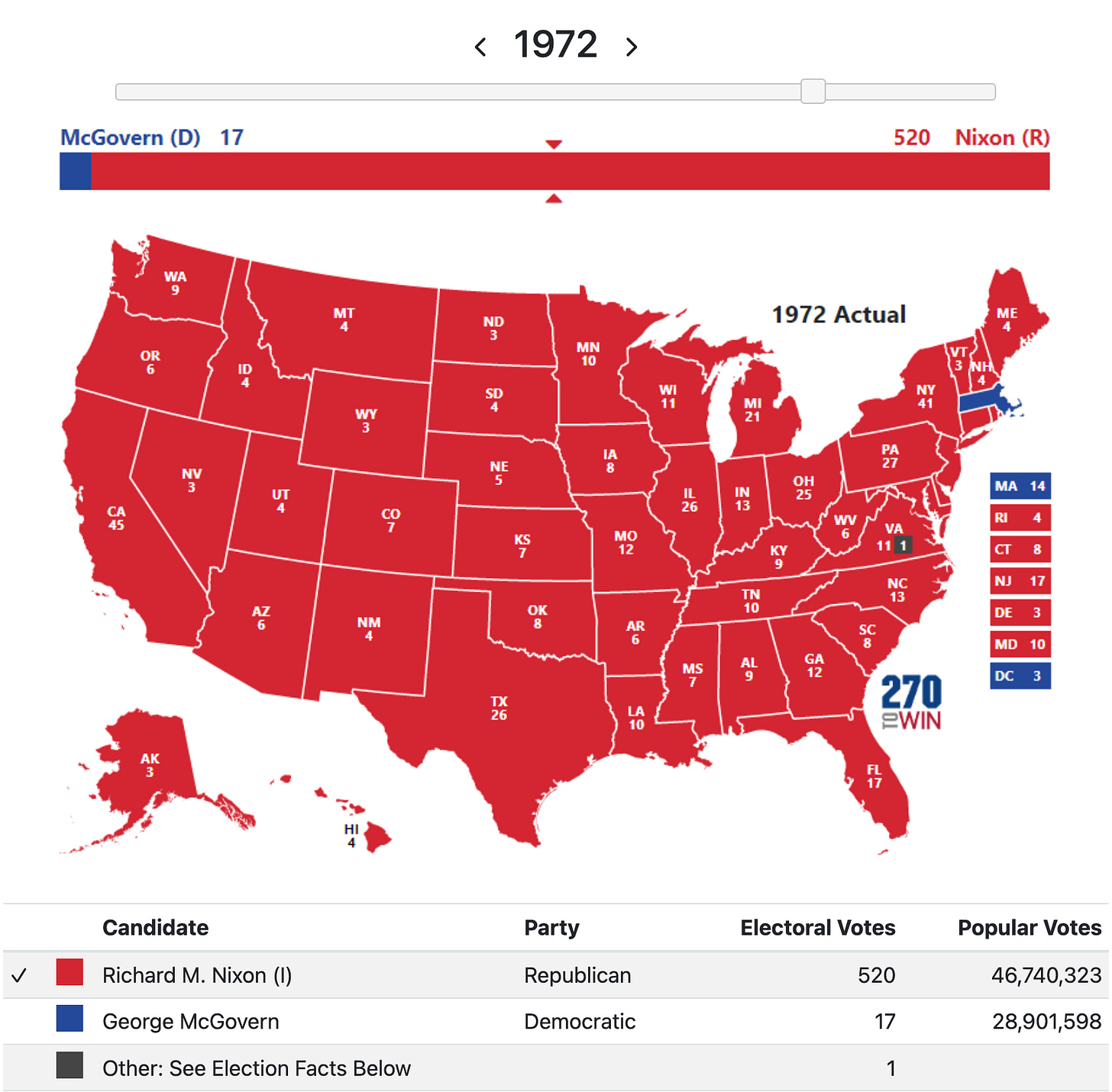

From 1972 to 1988, the Republican Party dominated the Electoral College map with decisive victories that turned much of the country into a solid red block for the presidential race (though Democrats controlled most of Congress for this period. Aside from Jimmy Carter's brief four-year break in 1976, the GOP won every presidential election in this period by landslide margins.

Nixon’s tsunami in the 1972 election set the tone for this era, with Richard Nixon crushing Democrat George McGovern in one of the most lopsided victories in U.S. history. Nixon carried 49 states, leaving McGovern with just Massachusetts and the District of Columbia. This made it clear that the Democratic Party needed more than progressive ideals to win over voters.

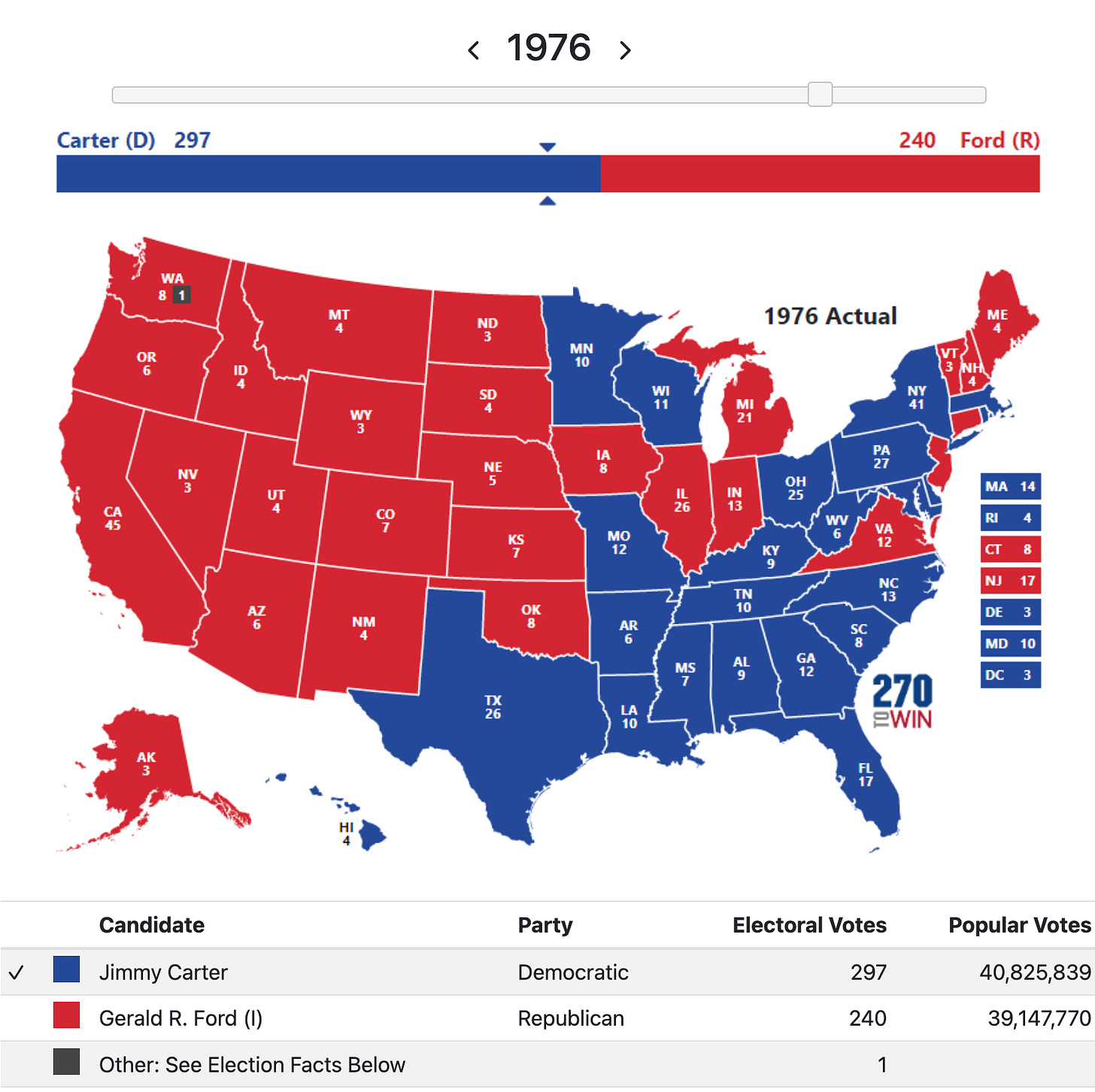

In 1976, the electoral map was like a homecoming party for the South. After years of flirting with the GOP, the region returned to its Democratic roots—probably because Governor Jimmy Carter of Georgia, felt like the guy next door (rest in peace, Jimmy). But because of the Watergate scandal reliable Republican States like Ohio, also voted for Carter.

It illustrates how, despite a 1.7 million popular vote lead, the election outcome could have been different if the key state of New York, or almost any two other medium-sized states—vulnerable under the Electoral College system—had shifted sides.

(As for Gerald Ford, pardoning Nixon wasn't a good look).

The 1980 and 1984 Elections

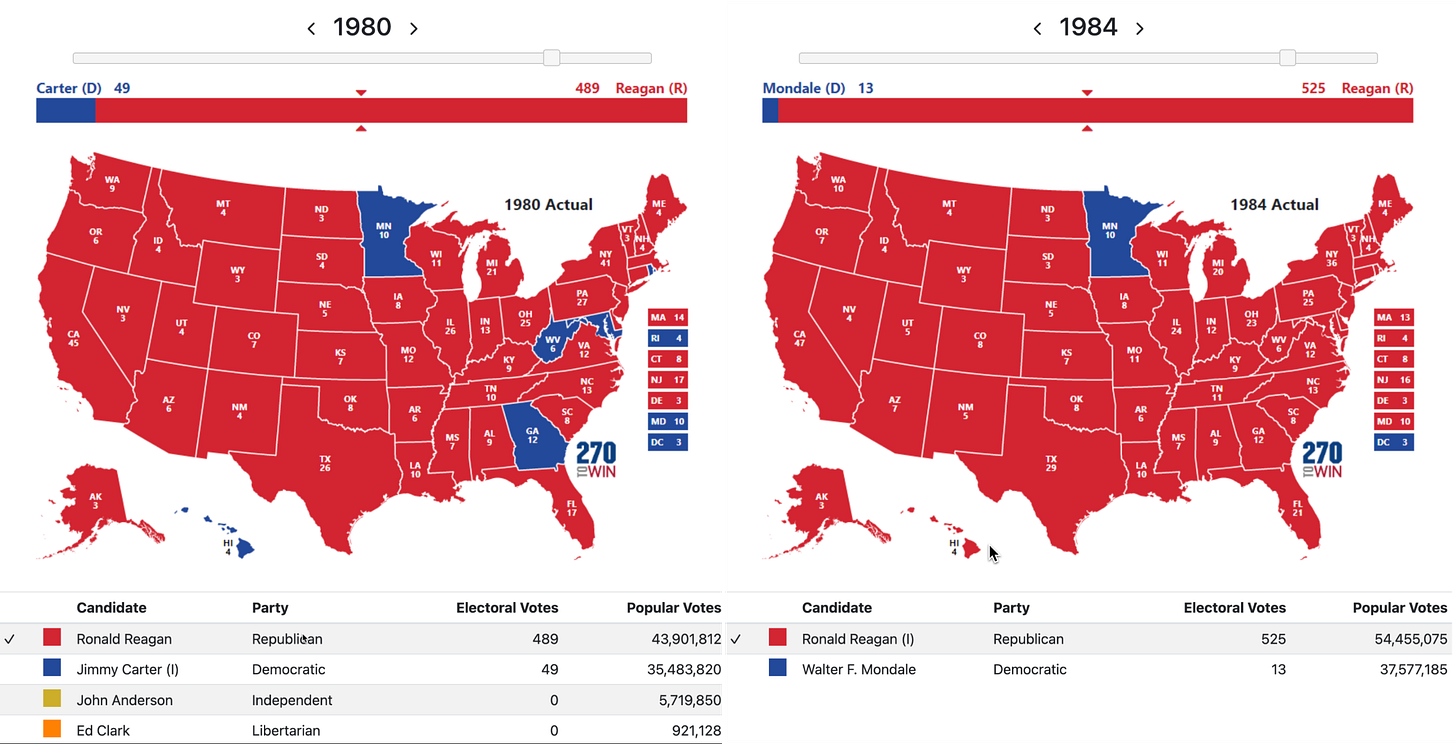

In 1980, Ronald Reagan’s Hollywood charisma and ability to connect with voters fueled his victory over incumbent Jimmy Carter, along with high inflation, high gas prices, and the takeover of the US embassy in Iran. He introduced the now-famous “Let’s Make America Great Again” slogan. The phrase resurfaced in Bill Clinton’s 1992 campaign and was later trademarked by Donald J. Trump.

Reagan’s brand of Republicanism swept the nation, winning 44 states and leaving Carter with only a few splashes of blue, including his home state of Georgia.

His 1984 re-election campaign was a masterclass in political domination, a 49-state landslide, with Mondale winning only his home state of Minnesota (by less than 4,000 votes) and the District of Columbia.

The 1988 Election

In 1988, Vice Presidency George H. W. Bush rode the Reagan wave to defeat Democrat Michael Dukakis. Bush was the first sitting Vice President elected to the Presidency since Martin Van Buren in 1836. The only other sitting Vice Presidents ever elected were John Adams (1796) and Thomas Jefferson (1800). In 1960, Vice President Nixon lost the election, and in 1968, Vice President Humphrey lost.

Bush promised to continue Reagan's successful policies, and voters responded by giving him 40 states. Dukakis's campaign struggled against Bush's sharp race-baiting attack ads (Willie Horton) and his portrayal as an out-of-touch liberal.

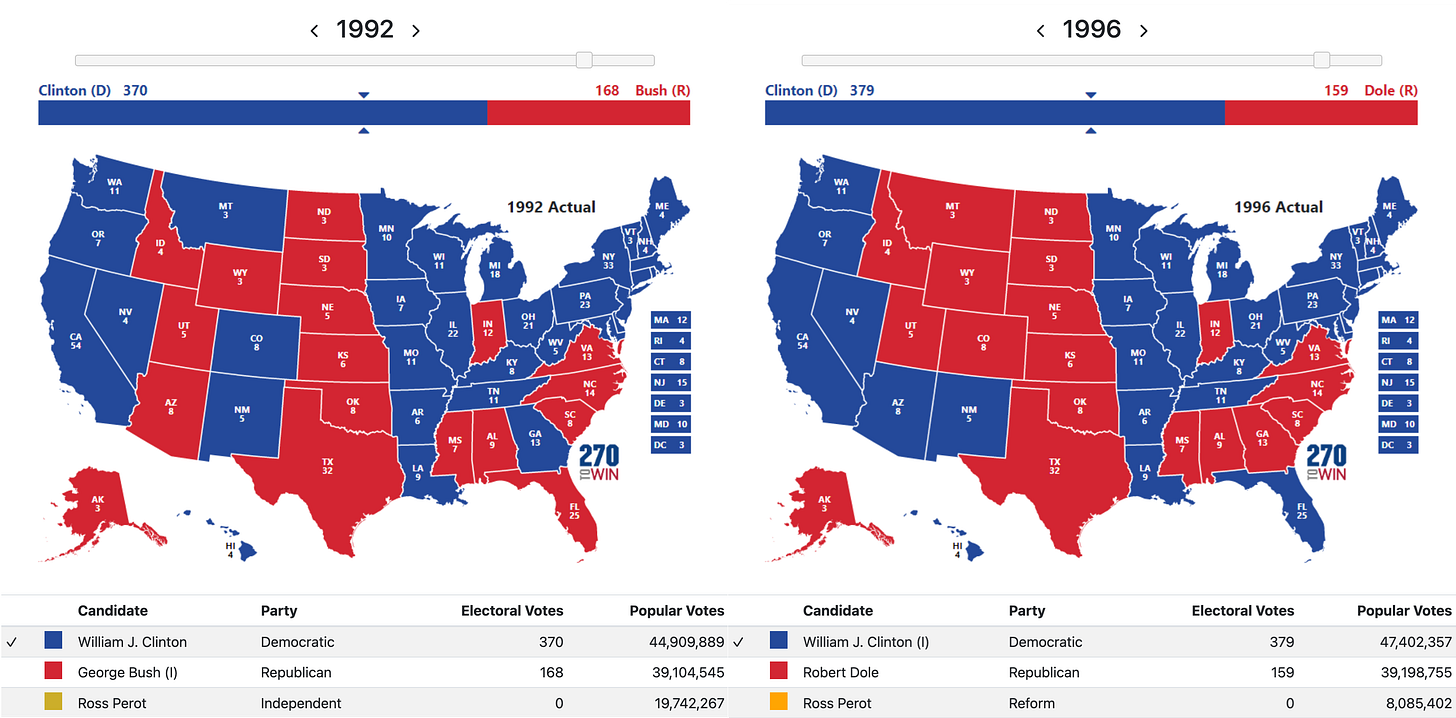

1992 and 1996 Elections

The 1992 to 2012 elections ushered in a more competitive era and a Democratic Revival. Bill Clinton, a charming Governor of Arkansas, delivered victories in 1992 and 1996, breaking the Republican hold on the South. When Clinton ran in 1992 there was high unemployment. Bush had promised never to raise taxes when he ran in 1988, but he reversed that policy and lost significant support.

The campaign of businessman H. Ross Perot garnered substantial votes in states like Nevada, Colorado, New Mexico, and Montana, likely helping flip those states to Clinton. However, in 1996, without Perot in the race, Clinton lost Colorado and Montana. Despite this, Clinton carried the West Coast, almost the entire Midwest, and the entire Northeast, breaking the Republican stronghold in the Midwest by losing only Indiana. In the South, Clinton consistently lost seven states from the former Confederacy in both elections, but he held onto his home state of Arkansas and his running mate’s home state of Tennessee.

The Electoral College map began to reflect the growing influence of the Sunbelt as states like Florida and Arizona became hotly contested.

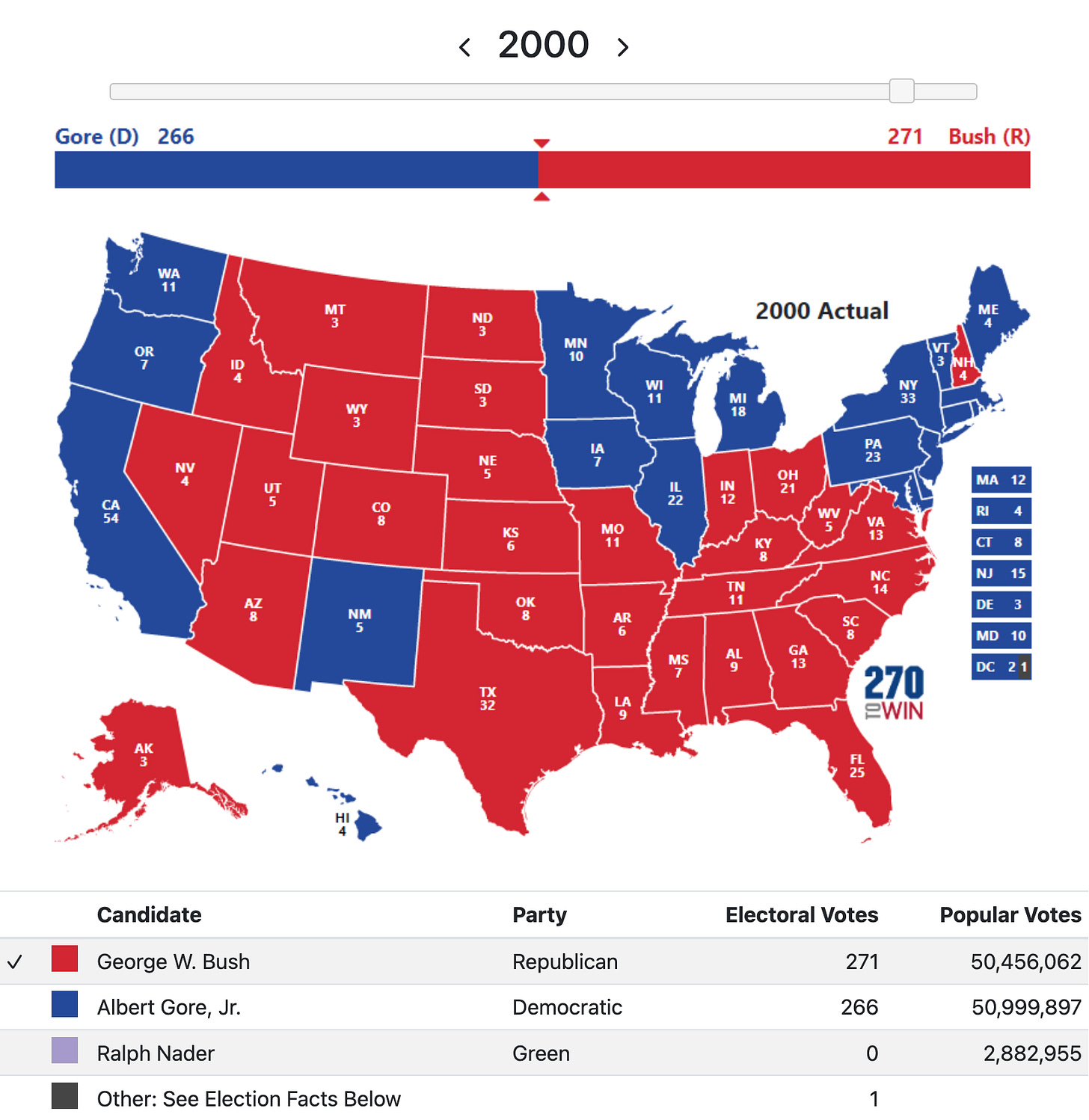

The 2000 and 2004 Elections

The 2000 election between George W. Bush and Al Gore became the ultimate case study in the quirks of the Electoral College. Gore won the popular vote by more than half a million, but the presidency hinged on the outcome in Florida, a state with 20 electoral votes.

What followed was a political drama featuring recounts, the hanging chad controversy, and a Supreme Court decision (Bush v. Gore) that effectively awarded Florida—and the presidency—to Bush. The final Electoral College tally: Bush 271, Gore 266 (with one abstention).

The debacle highlighted a key feature of the Electoral College: While millions of votes in reliably red and blue states had little impact on the outcome, Florida's razor-thin margin dominated headlines and determined the next president.

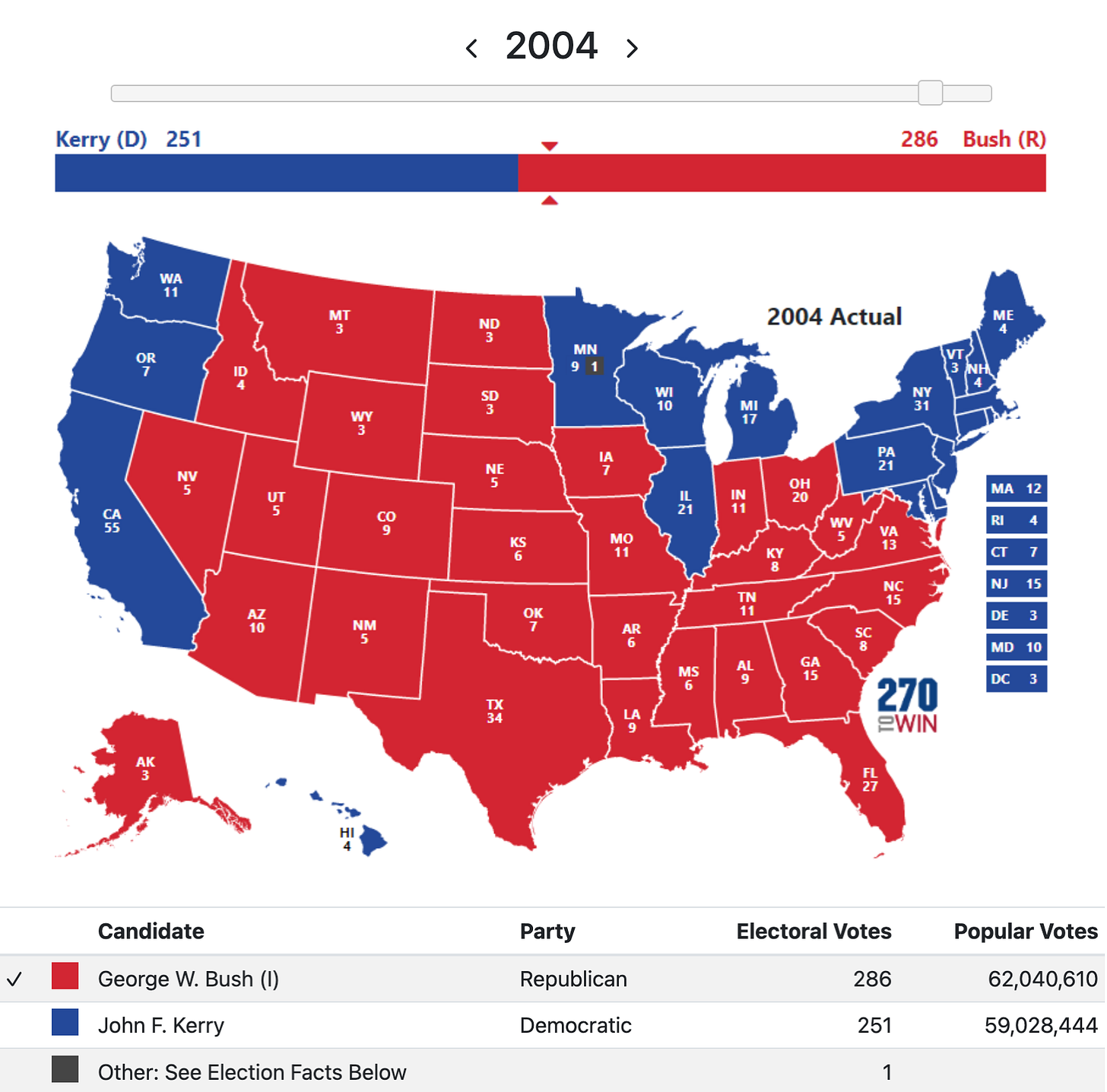

In 2004, the contest between George W. Bush and John Kerry was less chaotic but no less intense. With the nation deeply divided over the ill-advised Iraq War and domestic issues, both candidates poured resources into battleground states like Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Florida.

Ultimately, the election came down to Ohio. With its 20 electoral votes, the Buckeye State became the tipping point, giving Bush a victory with 286 electoral votes to Kerry's 251. Much like Carter's win in 1976, had just one state—Ohio—flipped, Kerry would have won the Electoral College and the presidency despite a 3 million vote deficit in the national popular vote.

The Electoral College cemented its role in making a handful of swing states the focal points of presidential campaigns.

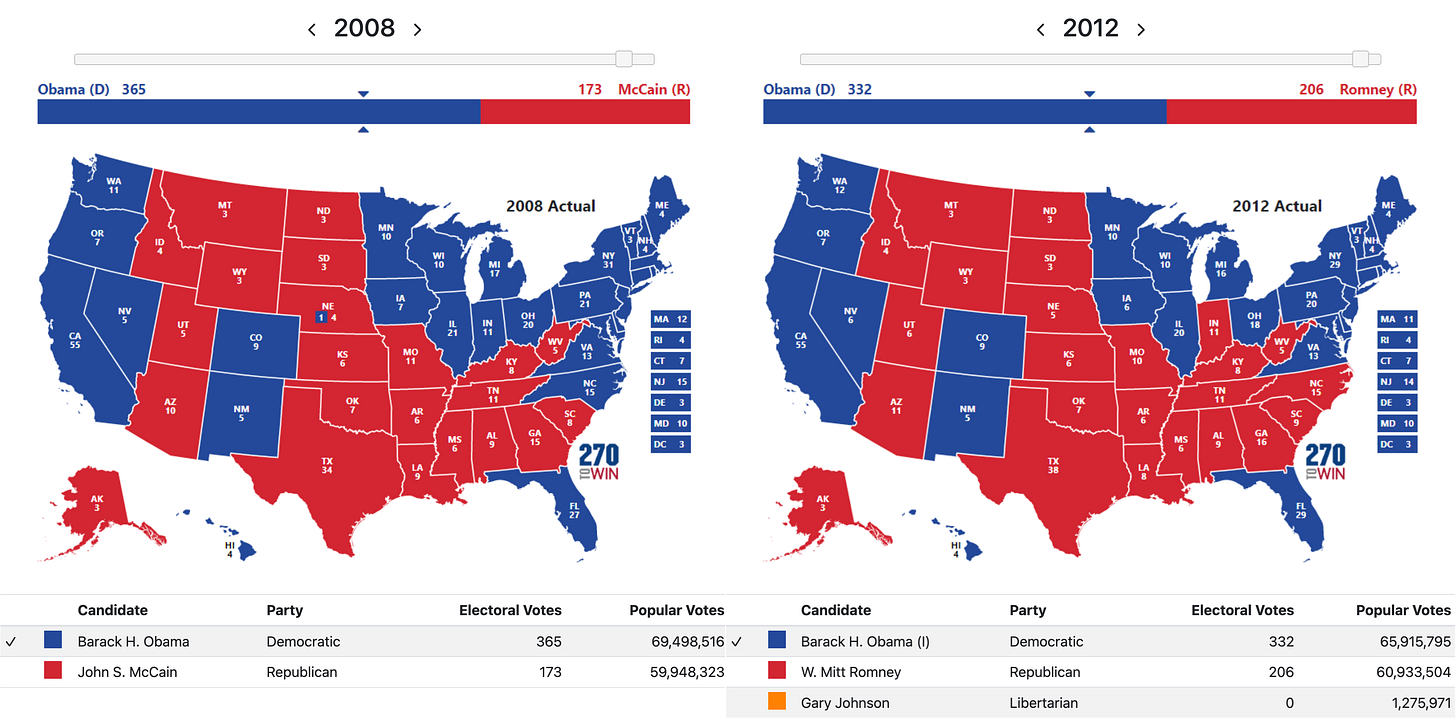

2008 and 2012 Elections

Barack Obama, the charismatic leader with his iconic “Yes We Can” campaign slogan and an army of celebrity endorsements, turned Florida, Ohio, and Iowa blue in back-to-back elections. He also carried Indiana in 2008, a state that had voted Republican in every election since 1940 except the landslide victory of Lyndon B. Johnson. The key to his decisive win was strategically targeting battleground states by mobilizing a diverse coalition of young voters, minority communities, and suburban moderates. He also used the internet to raise small donations from millions of people, whom political fundraisers usually ignored.

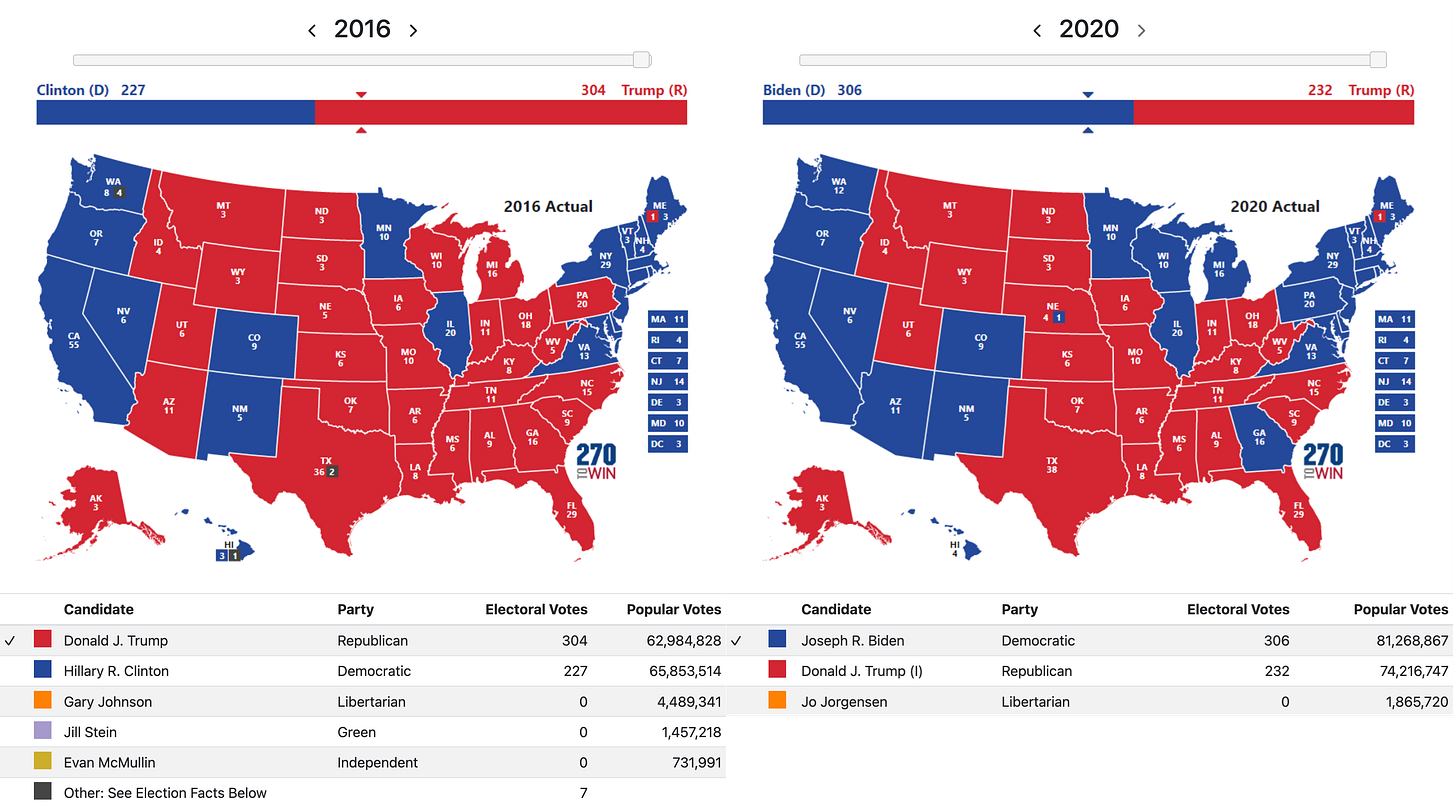

2016 and 2020 Elections

Donald Trump's shocking 2016 victory showcased, once again, the Electoral College's power to override the popular vote. Despite losing the popular vote by nearly three million ballots, Trump secured razor-thin wins in the key battleground regions of Michigan, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania.

Most analysts agree that Hillary Clinton’s 2016 loss was influenced by multiple factors, including gender bias and her lack of vigorous campaigning in Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania—the so-called "Blue Wall" that Democrats had depended on since 1992. In addition besides the three Reagan-Bush victories (1980-1988), no political party had successfully held the White House for more than two consecutive terms since Harry Truman’s election in 1948. These historical and strategic factors challenged Clinton’s path to victory.

In 2020, Joe Biden flipped those same Rust Belt states back to blue and won two key Republican Sunbelt states (Georgia and Arizona), winning the popular vote majority by almost five million and a significant majority in the Electoral College.

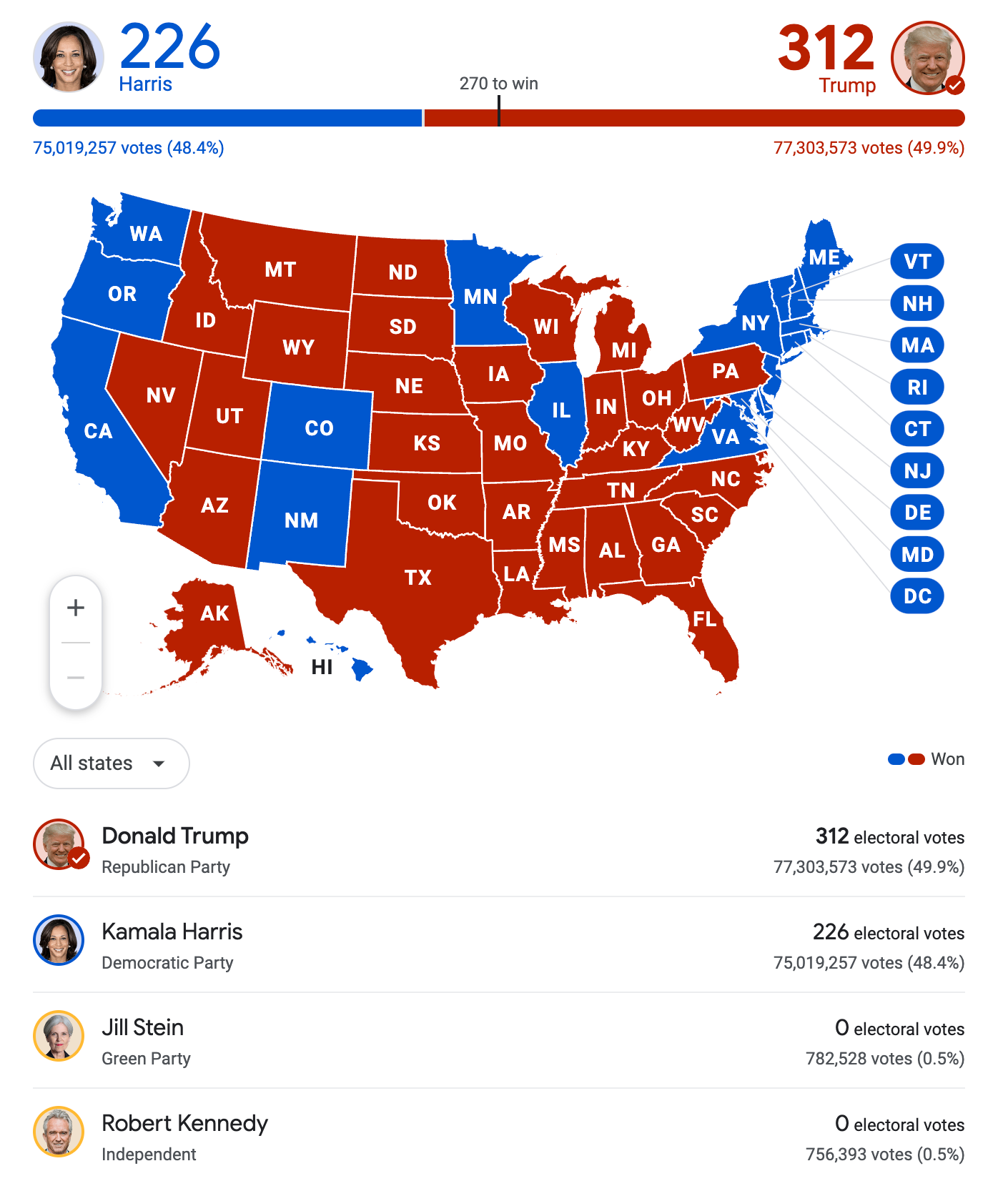

The 2024 Election

In the 2024 United States presidential election, held on November 5, former President Donald Trump defeated incumbent Vice President Kamala Harris. Trump secured 312 electoral votes to Harris's 226. Though the election has been characterized as a landslide, the election was close in the national popular vote. In the end, Trump received 77,303,573 votes (49.9%), Harris garnered 75,019,257 votes (48.4%), Jill Stein yielded 782,528 votes (0.5%), and Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. received 756,393 votes (0.5%).

The 2024 election saw a surprising setback for Democrats, with losses in Michigan and Pennsylvania—two Rust Belt states that had been pivotal to their coalition. Trump's success was marked by victories in all seven key swing states, including Arizona, Georgia, Nevada, North Carolina, and Wisconsin.

A shift in voter demographics was also significant. Trump made notable gains among Latinos, and several counties in Florida and Texas flipped Republican. Harris could not improve Biden’s margin with all demographics save college-educated women.

A Peek Into the Proverbial Crystal Ball

The purple frontier is shape-shifting. The emergence of new swing states like Georgia, Arizona, and potentially even Texas signals a more competitive ballot box in what have historically been "safe" Republican states. Some traditionally Republican-leaning areas are becoming more diverse, urbanized, and politically balanced, creating new battlegrounds that could decide future elections.

Ohio and Iowa, once key swing states, may fade into the background as their populations shrink and their politics lean more predictably red. However, the 2024 election saw a surprising setback for Democrats with losses in Michigan and Pennsylvania—two Rust Belt states that had been pivotal to their success.

In an era that leaves you dizzy with information overload, traditional news outlets are losing audiences to pundits and podcasters. The flow of reliable news has fractured, making deciphering fact from spin from fiction difficult. These echo chambers impact how voters perceive issues and, potentially, how electoral maps take shape. Swing states are especially vulnerable to targeted disinformation campaigns designed to suppress votes, sway voters, or energize the fringes.

The strategic use of disinformation amplifies the flaws of the Electoral College, as the effects could mean the electoral map may increasingly reflect not just demographic shifts but the success of fear-mongering and micro-targeted messaging that could sow deeper volatility, breed new battlegrounds and unpredictability among voter outcomes.

Billionaire CEOs are now lining up to use their financial power to shape electoral maps in subtle and overt ways, compromising the power of average voters, reshaping the democratic process and electoral maps into one where wealth wields disproportionate influence and an outsized ability to decide the country's future.

Then there's the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact. Most in this country are unaware of how this legislation is weaving through several states. If enough states join, it could trigger a seismic shift and entirely upend the traditional role of the Electoral College.

If enough states join this compact—representing a majority of the 270 electoral votes needed to win the presidency—participating states have agreed to award their electoral votes to the winner of the national popular vote (instead of the popular vote winner in their state).

The compact has 209 of the 270 electoral votes required to win a presidency. It has 75% of the total number of votes it needs to be enacted.

If the compact can attain the participation of states possessing 61 more electoral votes, the Electoral College map, as we know it, will be blown to smithereens. The "battleground state" phenomenon could fade, and presidential candidates might start showing up in Alabama and California to hold rallies, shake hands, and kiss babies.

If enacted, the compact would almost certainly ignite a legal firestorm, with opponents challenging its constitutionality in federal courts. Opponents might argue that the compact violates the Constitution's Compact Clause, while supporters would counter that state legislatures have the Constitutional authority to decide how they allocate their electoral votes.

How states award their electoral votes has changed throughout history, but today, the “Winner-Take-All” method is the norm in 48 states. Maine and Nebraska’s use of a congressional district-based approach shows that states can and do implement differing systems. The compact would represent yet another evolution in this process.

The U.S. Supreme Court has already signaled a willingness to uphold states’ authority in such matters. In the 2019 case Chiafalo v. Washington, the Court unanimously ruled that states can enforce laws requiring electors to follow the results of their popular vote. This decision indirectly supports that compacts like the National Popular Vote could fall within a state's constitutional authority.

I know. It’s a lot.

One thing's for certain: the debate over the Electoral College will persist. My "Electoral College" Google alert yields results daily for people calling to abolish the system and a few who praise it as a tradition as American as apple pie and Nathan's hot dogs.

Critics will continue to argue that it's outdated and undemocratic. At the same time, defenders will maintain that it protects the interests of smaller states (which it doesn't; we see clear evidence that it favors swing states). Whether through reform or tradition, the system will likely remain a focal point of American elections for years to come.

But if change is to come…change is best made from the people up.

Our responsibility is to be informed, challenge disinformation, and ensure our voices clearly articulate our desires. Only then can we be empowered to shape the evolution of systems like the Electoral College in a way that truly reflects the people's will.

Do you think our country will ever see a time when it is as united as it was at different points in America’s history, and why? Let me know in the comments.

If you’ve made it this far, thank you for spending so much time with me in an Electoral College map rabbit hole!

Very good synopsis of the EC situation. The premise of democracy is that all votes count the same. In practice, this rarely happens. In the US system, it is made worse by the electoral college, the legalization of bribes of government officials (lobbying and superPACs), as well as the compromises along the way like the Senate, where 2 senators that represent a few hundred thousand people in Wyoming have the same powers as the 2 that represent tens of millions in states like California, and more power if they stayed in congress longer, as they get "seniority" and the house and senate mostly make up their own rules as they go along, accountable to only their fellow conspirators. Add to that the fact that, in a democracy, the ultimate decision on laws rest with 9 unelected people who have life time appointments and are accountable to no one. Democracy, American style.....

This was a great read and got me down a Wikipedia rabbit hole about Barry Goldwater, which got me down another one about the Romney polygamist origins, and then Mormon polygamy colonies in Mexico. I learned so much from this!